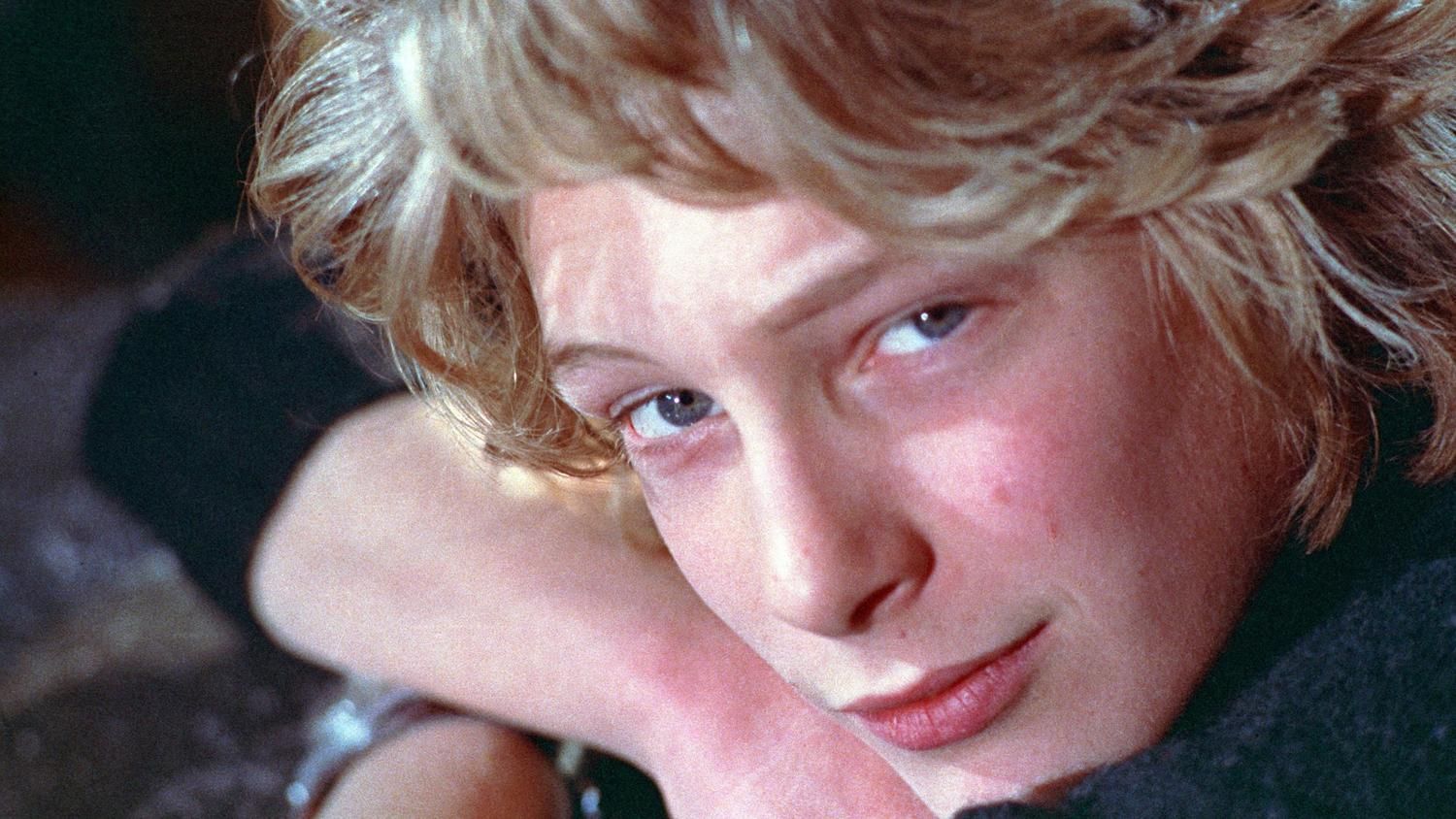

The Most Beautiful Boy In The World Review

If the Most Beautiful Boy In The World were a punctuation point that would be an ellipsis. Filmmakers Kristina Lindstrom as well as Kristian Petri have created an film, one of the portraits of Death In Venice actor Bjorn Andresen, who is a specialist in insinuation. They use the use of plain soundtracks and dramatic slow-motion in order to emphasize the stories that end up being atmospherically.

The topic -the plight of a child actor who, 50 years later, is still struggling with the basic issues of living — is so emotional that one could easily not give the film a chance due to the fact that it provides a narrative platform to Andresen currently 66 years old who lives in Stockholm. However, the techniques used in filmmaking are extremely heavy-handed, andmore troublingly — there's been no effort to assure the audience that during the production of this film, history hasn't repeat itself in the level of care given to the subject's mental health.

The overall picture is messy.

Two scenes from the two timelines of the film form the opening scene: an audition fifty years ago when Luchino Visconti asks an uncomfortable teenager Andresen to change into his underwear, and Andresen today, looking dreadful with a long beard that is white, and being a slob in his filthy house with the threat of being forced out. The current scenes are creepy and fake and cameras follow Andresen and his partner as they discuss what occurred to him five decades back, glancing through old newspaper articles.

The best parts are the archives: Super 8 footage from the film's set Death In Venice and of Andresen at home with his sister and grandmother who helped push him into the spotlight; press conference footage of Visconti in 1971 at the Cannes Film Festival saying, "He is getting older nowYou can tell that he's in a awkward position," to a roomful of journalists who laugh while Andresen is seated, uninterested.

Lindstrom and Petri discuss the ostracism of Andresen's fame, the photo shoots, his fandom in Japan and a brief musical career that creates a numb feeling in the sense that his youth — which the film slams is recreated through a series of voyeuristic images as his narrative reveals sadness and loneliness. The relationships with men of a certain age are alluded to, but not in the fullest detail. The tragedies that have shaped his personal life are recited. The portrait overall is a mess but the elements that are visible form a compelling claim of innocence that points a finger at an industry and a society that puts celebrity over well-being.